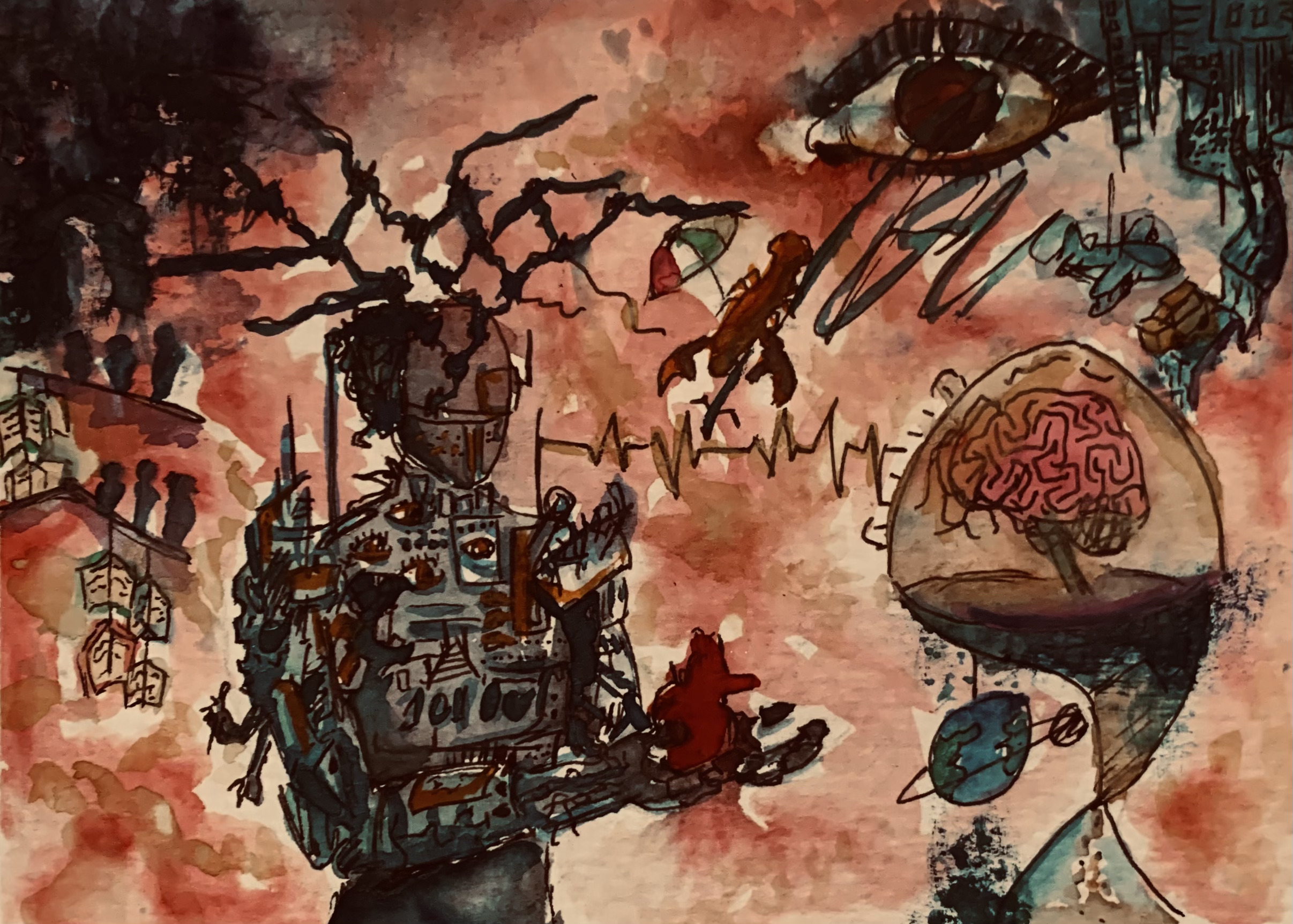

What is artificial intelligence?

Most artificial intelligence systems are built on artificial neural networks, which are circuits similar to neurons in the human brain. Layers of artificial neurons intertwine and interact, cascading signaling information from one neuron to the next. With this system, AI can learn information, reason, and problem-solve. However, computer scientist and AI researcher at MIT, Lex Fridman, suggests that the purpose of AI may be greater than to carry out computational tasks, but rather to understand what intelligence is and to unravel how the human mind works.

One question is, if the neural networks in AI and humans are significantly similar, can AI exhibit characteristics of the human brain such as emotionality and consciousness? This leaves the primordial questions: what is emotion? what is consciousness? Is there a way to explore such questions beyond arbitrary philosophy, instead deriving a materialistic and tangible way to engineer such behaviors?

What is emotion?

A brief article on the basics of emotional psychology by the University of West Alabama’s psychology department defines emotion as “a complex reaction pattern, involving experiential, behavioral and physiological elements.” The first part of emotion is the subjective experience, where a perceived stimulus causes an emotional reaction. Another component is a physiological response, a subconscious, physical activation of increased attention or arousal throughout the nervous system. The last event is the expression of that emotion, a way of transmitting that emotional signal to other entities, as humans do by conjuring facial expressions, laughing, crying, etc.

Following this definition, emotions are subconscious reactions to stimuli (a stimulus meaning a change from the current state). However, if every stimulus, which there can arbitrarily be an infinite number happening at once, causes an emotional response, there can be an infinite number of emotional responses occurring at the same time. It would be too perplexing to sort or identify; therefore, there must be some spotlight system that can direct attention to only a particular emotion. But how is it possible to determine which emotions are relevant and which ones should fade into the background?

What is relevant? The frame problem.

Professor of Cognitive Robotics, Murray Shanahan, in a Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy publication, explains this as the frame problem: “Only certain properties of a situation are relevant in the context of any given action… For the difficulty now is one of determining what is and isn’t relevant.” Imagine picking up a pen. What makes that object a pen and what separates the pen from everything that isn’t a pen? Is there a boundary? This might seem like a trivial question, but it is not clear what mechanism in the human brain makes humans perceive objects in the world as individual entities. Further, what makes it so that the object appears as a pen and not plastic or metal or its physical atomic constituent? Humans do not perceive objects merely for their material parts, but rather as tools.

Teaching AI meaning

Such is the problem with training AI. How do you teach a system to interpret not just the physical makeup but the meaning of the objects? What is it that makes two things similar and two things different? Fridman describes an example of this implication when teaching an AI system to learn what a cat is. Is the cat just the boundary of the body within the 2D image? Is it just the face? Is a cat just something with ears? How is a cat different from a dog? Does having four legs make two things similar? The answers to these questions are not so obvious and are rather ambiguous: how many catlike features does a cat have to have for it to be a cat? How many uncatlike features does the cat have to have to not be considered a cat?

Essentially, social constructs and universally believed symbols and words are used to identify objects. In other words, there is a universal definition (of a cat) and the AI, like a young child, learns arbitrary associations between words to the physical object it describes.

Interpreting images

This means that when AI is shown an image, it must not only remember features (ears, fur) but understand the object’s socially constructed purpose (cat, pet). For AI to be useful, the associations between words and objects must be in sync with humans so that the AI and the user are talking precisely about the same thing. But if the AI is given images, what does it mean to understand one particular thing? And again, how do you pick out what is relevant in any given frame?

Solution: Consciousness

John Vervaeke, philosopher and cognitive scientist at the University of Toronto proposed that the solution to distinguish relevance is consciousness. Analyzing the global workplace theory initially proposed by cognitive scientist Bernard Baars, Vervaeke makes the analogy that consciousness is like the computer desktop, a visible screen on which you can retrieve files from memory, edit and tweak details, and return the file back into memory. Then, you can open another file on the desktop for rationalizing and considering. The desktop grants the capacity to look back in time and imagine far into the future (looking at stored files, and creating plans).

This allows the desktop to work like a lucid consciousness. This is significant because many parts of the computer are running at the same time: the hard drive, memory, graphics card, and multiple programs; however, the desktop focuses a spotlight on one particular file at a time, establishing the relevancy and reality of that one event. This is similar to the way the human conscious accesses memories. When you remember or think about something, there is a spotlight on that event.

Consciousness in the brain

Similarly, not all of the brain is working at the same time nor is the entire brain conscious. For instance, the cerebellum, a structure in the back of the brain, which consists more densely of neurons than the entire cortex, is unconscious. As clinical psychologist Jordan Peterson pointed out, this suggests that consciousness is not a mere consequence of neural activity. Consciousness does not simply arise in the course of evolution, by chance. Animals do not spontaneously become conscious. This means that the aforementioned neural networks within AI cannot simply be stimulated and evolve a consciousness over time. However, if a consciousness cannot be stimulated, can emotion? Can AI be taught to understand emotion?

To understand something

The first part is defining what it means to understand something. Peterson describes that understanding is the alignment of different modes of thinking, particularly the semantic, visual, and physical. Suppose you are in a woodworking shop, and the master is trying to teach you how to use a saw and how to avoid hurting yourself. The master might tell you a story about how they hurt themselves and what behaviors you must do to avoid injury. But what does it mean if you understand what the master is telling you?

First, you would use your semantic intelligence to analyze and remember the master’s words and sentences. Then, you would convert these words into a visual representation of the story in your brain to imagine what behaviors, body movements, and objects have led to the injury. Lastly, to prove your understanding, you would physically act out the behaviors that prevent injury. In this way, you have synchronized the semantic (words and symbols), visual (images), and physical (bodily acting out proper behavior) to understand something. If you failed to physically act properly, you would injure yourself, and you wouldn’t have understood your master.

Origins of emotions

The next questions are why would emotions originate and is it possible to replicate that prerequisite state for emotional development in AI? In The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, evolutionary biologist Charles Darwin theorized that natural selection (that favorable genes and traits are passed down) extends as much to the mind and behavior of animals as it does to physical traits, suggesting that emotions are inherited from species as survival mechanisms. With this definition, emotions don’t require conscious observers, because animals have emotions and no consciousness. Combining Peterson’s three conditions for understanding and the survival necessity of emotion, the fundamental characteristics of emotion in the nervous system can be explained with entropy and the free-energy principle.

Architecting emotions in cognitive systems

The oversimplified free-energy principle, which was proposed by cognitive neuroscientist Karl Friston, is that emotions can be attributed to entropy, a physical quantity, within a cognitive system. Entropy is the natural tendency for chaos, disorder, randomness, and unpredictability. To combat entropy, the brain sharpens perception and optimizes action for survival. Perception configurates synaptic activity (stimulation of neurons), learning and memory, and attention and salience. Perception analyzes which neurons were stimulated, how this relates to the existing interconnections between neurons, and if there is a focus on certain stimuli and not others. Using this information, perception creates a representation of the sensations and their causes, stimulating optimal action.

The quantity and necessity of predictions are correlated to entropy. The higher the entropy, the more surprise and unpredictability; this corresponds with increased neural perception and action. For this reason, surprise and most negative emotions are defined by high entropy. For instance, anxiety is the emotional response to an increase in unpredictability in the future (entropy), when everything seems out of control. Conversely, positive emotions, such as moving toward a goal, decrease entropy, and increase order. Using this logic, entropy within neural networks and information systems can correlate to various emotional responses.

Afterthought.

Another relationship between entropy and emotions involves the second law of thermodynamics, which states that entropy in the universe is always increasing. The question is, if entropy is always increasing, and if negative emotions increase entropy, then did negative emotions inevitably arise to fulfill the second law of thermodynamics? Do emotions always arise in species as a method to increase the natural order of entropy? Is there something more to emotions than the survival instincts in social species?